The Salmonella Outbreak No One Knew About

By Laurel Maloy, contributing writer, Food Online

State and local public health officials have a responsibility to inform the public. In this particular incident… it didn’t happen

During the summer of 2014, 21 people fell ill after eating at Brent’s Deli in Westlake Village, CA. However, no one, except the people who suffered, the public health officials, and the owners of the deli were ever made aware of the outbreak.

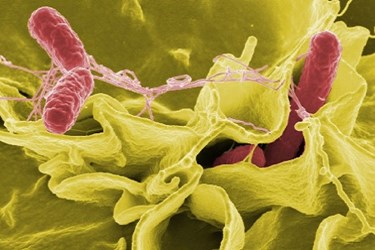

The outbreak first came to light when seven people living in Ventura and Los Angeles counties were identified as being infected with a somewhat uncommon genetic strain of Salmonella Montevideo. Patient interviews turned the attention to Brent’s Deli. Eventually 19 patients were diagnosed with S. Montevidea (JIXX01.0645), and another two diagnosed with JIXX01.1565, a clonal offshoot of the outbreak strain. The strains were positively identified through the use of pulsed field gel electrophoresis (PFGE) performed by the California Department of Public Health’s (CDPH) Microbial Disease Laboratory (MDL). Two of the infected patients were employees of the deli. And still, the outbreak was kept under wraps, a remarkable feat in and of itself when you consider the speed with which information normally travels today. If just one ill person had posted about it via social media, this outbreak would not have gone unnoticed.

According to Bill Marler’s Blog, he was notified by Trevor Quirk, a California attorney, who was retained by one of the outbreak victims. Bill Marler is a food-safety litigator and considered a pioneer in his field by the National Law Journal. His Seattle-based law firm, Marler Clark, has been responsible for successfully litigating nearly every major foodborne illness outbreak across the nation. They are now litigating this one as well.

The timeline for this outbreak is laid out here. The onset of illnesses occurred on April 30, 2014, with illnesses from this same outbreak being identified as late as August 16, 2014. The largest numbers of patients were reported in June and August, with eight patients requiring hospitalization. What stands out is that though the onset of illness can be tracked back to April, with a significant cluster in June, it wasn’t until mid-July that the MDL raised the level of awareness. Apparently the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) was never brought into the loop.

On July 9 the Environmental Health (EH) staff of Ventura County performed an on-site inspection at the Deli. During the inspection, numerous violations — including sanitation, storage, and cooling problems — were discovered. The manager was directed by EH to immediately take action to correct the violations. A follow-up inspection occurred on July 22, with major violations again observed and annotated. High-risk foods were not stored at or below the recommended temperature, nor were they cooled properly. One employee was guilty of not washing his or her hands prior to handling food or utensils and the cleaning cloths were not sanitized properly between uses. Plumbing fixtures were found to be leaking and in general disrepair, and a refrigerator was found to be defective. Flooring was broken, preventing proper cleaning. Another inspection was then conducted on July 29, during which the violations appeared to have been corrected. But then, due to continuing illnesses, another inspection occurred on August 11, causing the deli to be closed on August 12. Brent’s Deli hired a third party to oversee cleaning while employees were required to attend classes focusing on acceptable food-safety procedures. One day later, on August 13, the deli was allowed to open its doors after environmental and food sampling found no trace of salmonella. However, two employees’ hands did test positive for the S. Montevideo strain, JIXX01.0645. The deli was under close scrutiny by EH throughout August with another formal inspection completed on September 12, with no violations being noted. The case was considered closed on October 1, after no illnesses had been reported since the last on August 10.

Though it may seem surprising that this outbreak was not elevated to warrant at least a local news report, no laws were broken. Unless an outbreak involves a large number of people or affects people in many states, Federal agencies, such as the CDC, may or may not be called in. The question then, is: “How many people constitutes a large number?” It is also common for a state health department to work with the state department of agriculture when more than one city or county is involved. That did not happen, though two counties, Los Angeles and Ventura, saw patients.

The CDC defines a foodborne-disease outbreak (FBDO) as “an incident in which two or more persons experience a similar illness resulting from the ingestion of a common food.” If you look at the timeline, one case was identified on April 27, another on May 18, one on June 1 and then two on June 8. The largest number of confirmed cases, three, happened on June 29, but no action was taken until July 18.

Consider this — what if the unsanitary conditions at Brent’s Deli was discovered before the outbreak? These conditions evidently existed, but went undiscovered, for an extended period of time. An unscheduled short visit from EH would have led to a more thorough inspection. What if, after the first two cases, someone had thought to warn the public or to immediately question the patients on where they had eaten? What if the first inspection at Brent’s Deli had been conducted in early June, rather than in late July? There are any number of solutions that could have been implemented to prevent illnesses.

Anyone in the food-processing industry — from farms providing processors with raw products to the delivery person that supplies corned beef to the local deli — has a moral responsibility to report. The industry can, to a great extent, police itself. It simply takes a commitment to be aware and to get involved to prevent the blatant conditions that cause foodborne illnesses, hospitalizations, and death.